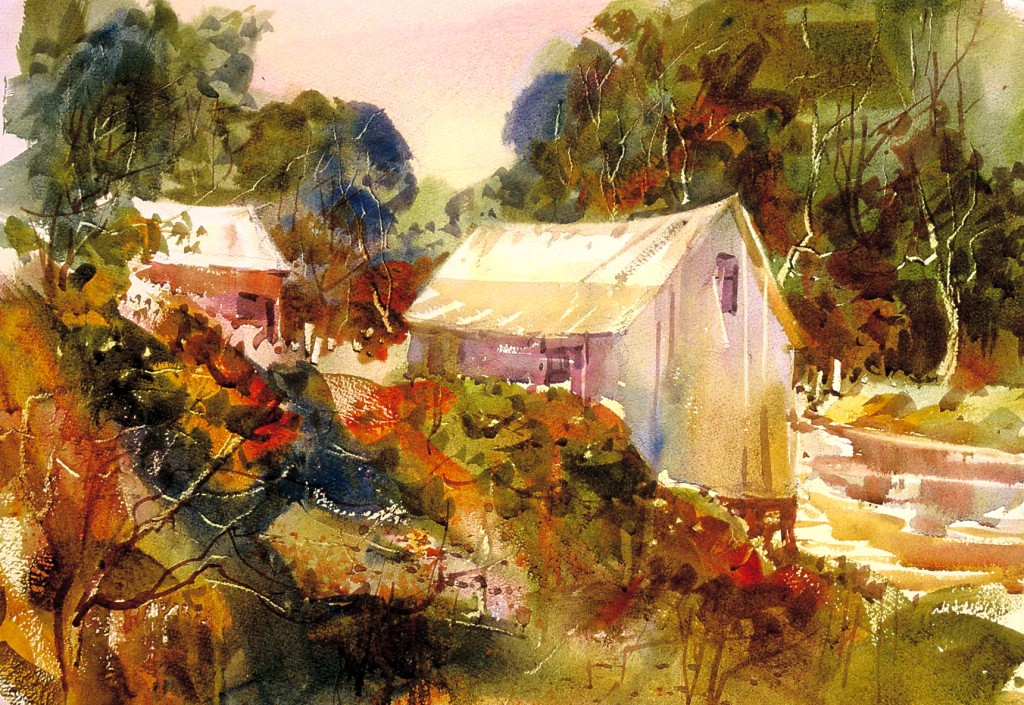

(15 x 22 watercolor on paper “Plum Island”, I really got involved in the texture of the trees and tried to emphasize the overlapping shapes and textures in the trees. I worked at varying the strokes to create variety and interest.)

Although it is sometimes not what we notice first about a great watercolor painting, expressive brushwork is one of the most important qualities of a good work. Due to the fact that watercolor is fairly hard to remove from the paper and is somewhat less workable than oils, pastels, graphite and to some extent acrylics through the use of overlaying opaque colors on top, it is critical that you begin and end the painting with solid and creative brushwork. It will be very difficult to correct sloppy and repetitive brushwork in those major areas of the painting. Think of the trees you have painted with brushwork that evoke the look of a broom, not an elm, or the water you painted that has the feeling of a parking lot, not a tranquil pond or the light on the side of a model’s face that looks like an advertisement for a beard commercial and you will understand that your skill with the brush is a critical factor is expressing your creative intent. Now I must say that there are times when you apply paint in big washes or solid color forms without a major concern for the individual brushwork, but you still want the brushwork in the these forms and pieces of color to be reflective of your intent for this area of the painting and not be cluttered movement, conflicting movement or unintentional texture.

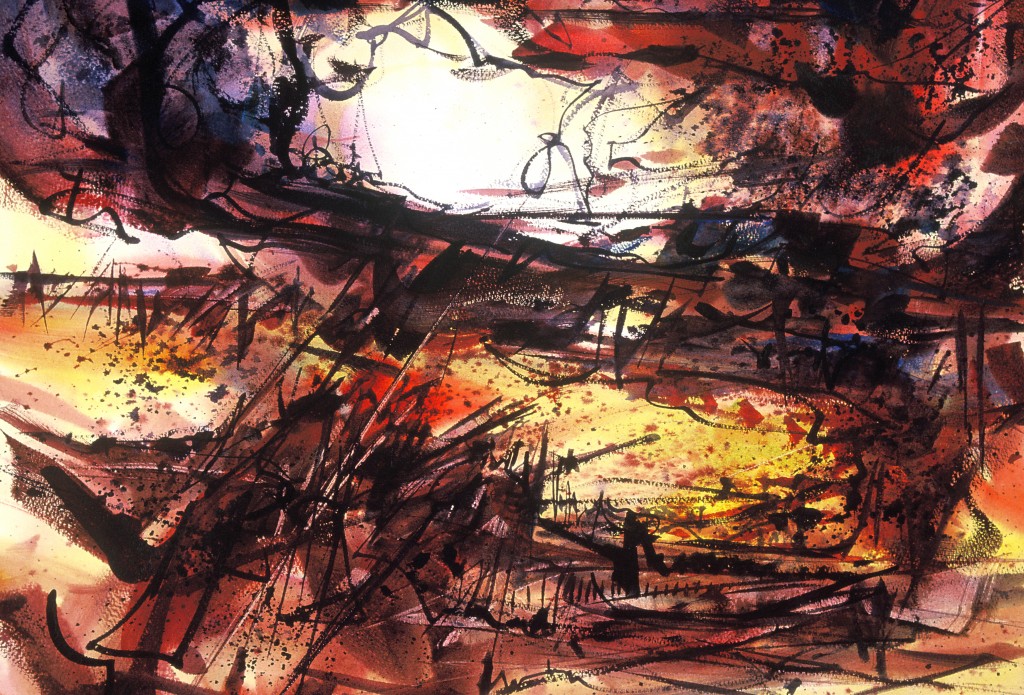

(22 x 30 watercolor on Paper, “Setting Sky”, This painting is definitely an example of expressive brushwork although done exclusively with a 1.5 inch Robert Simmons Sky flow. I think you can see that the movement in the sky and landscape is amplified by the bold application of paint.)

If brushwork is not an important consideration in your painting then your work will not have the finish or quality of a masterful painting. Learn to apply your paint with a purposeful and deliberate brush stroke and try to avoid continual rubbing onto the painted surface with a wet and soggy brush. Get in the habit of thinking about the brushwork before you touch the paper and then have a confident and direct approach when your brush is in contact with the paper. The brush is the extension of your creative intent — it is your partner in the process, not just a stick with hair on it. Until we get to the point of painting with our hands and feet, the brush is the major way that the paint will get on the paper and the painting will always record for the viewer the skills you possess in brushwork. Neglecting the improvement of your brush skills will always hold back your painting progress.

Ways to improve your brushwork. First it is important to understand the factors that control the expressive marks you want to learn to produce.

- Type of brush. If you are like me you have a multitude of brushes in your bag and you have your favorite few with which you have a relatively good relationship. Each brush type whether it be flat or round, natural or synthetic, big or small has a range of marks it is capable of producing. There is quite a bit of overlap in the type of marks brushes will make for the painter who will take the time to practice with each of the brushes in the bag. Some of these strokes are very familiar to you but I am quite sure that most painters have not really experimented with all of the favorite brushes to really see what they will do. I think it is amazing how many brushes some of my students have and how few they really use. The common statement I hear is “Gee I really don’t like a round brush, they don’t work for me” or “flat brushes always make the same type of mark” or “I don’t have any control with that big brush so I use this small one”. These statements or this type of thinking leads us to buy a special brush for each specific problem when it would be a better idea to develop a varied repertoire of expressive marks using only a few brushes. I am convinced that John Singer Sergeant could come back from the dead and do quite well with just a few sable rounds. Take the time to bond with your 1” flat sabeline, your #12 sable or white sable round, a 1.5 inch white sable wash brush and maybe a #4 rigger and your paintings will definitely improve. Think of them as the main tools in your tool box and then get some real mileage out of them — don’t move to new brushes until you can make these few really do the job in your paintings.

(22×30 watercolor on paper, “Life Begins” A painting in my creation series which will be highlighted in the portfolio section soon. This painting was achieved by splattering the paint on to the paper with a wash brush and pulling a really long rigger across the surface of the paper. I tried to evoke the feeling of the DNA strands and jumping from single cell to multicell organisms.)

(22×30 watercolor on paper, “Life Begins” A painting in my creation series which will be highlighted in the portfolio section soon. This painting was achieved by splattering the paint on to the paper with a wash brush and pulling a really long rigger across the surface of the paper. I tried to evoke the feeling of the DNA strands and jumping from single cell to multicell organisms.)- Angle and edge. Brushes are very creative tools in the painting process when they are used by an artist who thinks about a variety of contact possibilities for the brush. Each brush has several edges to use and by exploring the different marks that can be made by each, your paintings will have a much more enlivened application of paint. Try not to use the same edge repeatedly because this will lead to a tired and boring style. Also experiment with the pressure or amount of brush surface you are using. To complement your understanding and exploration of the edge, put more focus into pushing the brush in and out when in contact with the paper. Most brushes can take a whole lot more abuse than we give them — just remember to not put so much pressure on the bristles that you permanently break the bristles at the ferrule. One last word of caution, when you are using a round brush or for that matter a flat brush, try not to paint too much with just the point because this will prematurely wear down the point. It is a better idea to paint with the side of the brush pulling it to the point, which keeps the bristles longer and the edge or point more defined and perfect. You can definitely use the point for those moments when it is required but keep it to a minimum.

- Amount of water in brush and on paper. The secret of watercolor painting is understanding the relationship between the amount of water in the brush to the amount of water on the paper. When experimenting with your brushes is the time to really pay attention to this secret. Any brush will make a completely different type of mark when it is fully charged with water than when it is dry. It will also make a totally different type of mark when it is stroked across a wet, damp, or dry piece of paper. The amount of pigment in the brush also factors into the quality or character of the brushstroke. To really get the brush working for you in your painting you have to feel totally comfortable painting on the ever changing surface of the paper. For me it is not as desirable to wait for the paper to dry before I move from stage to stage in the painting — I want to be able to keep right on working. I have learned to do this by practicing using a brush and applying pigment continuously throughout the painting process whether it is on wet or dry paper. I have found I can regulate the amount of water or pigment in the brush and be fairly comfortable painting whether the paper is wet, dry or somewhere in between. But I have to pay attention to the conditions on the surface of the paper and regulate the brush accordingly. Variety and creativity will be the result in your paintings if you work on changing the amount of water and pigment in your brush and paint on different types of surfaces.

- Speed and direction of the mark. The faster the brush moves across the paper the less time there is for the paint and water to come off onto the paper. Practice using a fast pass across the paper and you will begin to see the wonderful textural effects you can achieve. Also by moving the brush quickly you can highlight a damp or wet area with a color and not have the usual explosive blossoms that are so problematic. I have found I can use the speed of the brush to put glisten on water or to highlight the light in trees without having to wait for the paper to dry. This does take some practice.

- Distance from paper and arm movement. For me there is no way I can really get into the painting process and develop expressive brushwork if I am sitting down and I am too close to the paper. I need to be able to get back from the painting and really get my arm and wrist working for me. I never hold my brush like a pencil I hold it like an extension of my arm and I work on achieving a fluid and rhythmic painting motion. I believe this keeps me involved on all levels when I paint and the movement is translated into my expressive brushwork. If you are so close to the paper that you feel cramped your work will show it. Your brushwork will be tight and tedious and your painting will lack rhythm and movement. If you can’t stand up for physical reasons at least try to get back from the painting when you work. I always keep in mind that the brush is one of my most important tools I can use to translate my creative intention to the paper so I want to give it the most freedom and possibilities I can.

(15 x 22 watercolor, “Late Day Pemaquid”, I used the side of a number 16 round brush to skip the paint across the water to get that feeling of afternoon glare. I came back on top to the textured wash with the same round brush and laid in the moving marks to create the feeling of the water undulations.)

(15 x 22 watercolor, “Late Day Pemaquid”, I used the side of a number 16 round brush to skip the paint across the water to get that feeling of afternoon glare. I came back on top to the textured wash with the same round brush and laid in the moving marks to create the feeling of the water undulations.)

Exercises

- Make as many brush marks as you can with all of your favorite brushes. Think of all of the factors listed above. Work on dry and wet paper and keep working until there is no white paper left. This is not about making paintings — this is about learning how to make creative marks and to develop a mental library of things you can do to create texture and interest in your washes and shapes.

(18 x 24 watercolor, “Beethoven’s Symphony Number 6”, I turned on the CD and played with a flat brush and just let it go. It helps to like the music.)

(18 x 24 watercolor, “Beethoven’s Symphony Number 6”, I turned on the CD and played with a flat brush and just let it go. It helps to like the music.)- Visualize a subject and make all of the marks that evoke the essence of the subject. Remember some subjects will require overlaying of washes and marks to really describe the object. Be creative not literal.

(15 x 22 watercolor, “Rockport” definitely about the expressive uses of the brush with very little exact detail. You should have fun with this lesson.

(15 x 22 watercolor, “Rockport” definitely about the expressive uses of the brush with very little exact detail. You should have fun with this lesson.- Learn to use two brushes, one flat and one round, better. Make every type of mark with these two. Try to duplicate the same type of marks and shapes with each. It is possible to come close to painting exactly the same types of shapes and marks with a flat and a round but it takes practice.

(18 x 24 watercolor, “Through the Trees”, this painting came about as a result of this lesson. I just started painting thinking about trees, light and distance, and although speed is not the goal in painting this one was done in about 15 minutes. I can’t say enough about practicing brushwork and application of paint on all surfaces wet, damp and dry. Through these lessons I have learned to paint without a hair dryer.)

(18 x 24 watercolor, “Through the Trees”, this painting came about as a result of this lesson. I just started painting thinking about trees, light and distance, and although speed is not the goal in painting this one was done in about 15 minutes. I can’t say enough about practicing brushwork and application of paint on all surfaces wet, damp and dry. Through these lessons I have learned to paint without a hair dryer.)- Wet to Dry overlay. This is a great lesson to combine both brushwork, value control and movement across the paper. Begin on wet paper and just start making expressive color washes and splatter marks — leave some large varied pieces of white paper. Immediately follow this without letting the paper dry, using expressive and varied brushwork. Try to think only of movement and creative line. Begin to cut away at the white paper creating more interesting and dramatic shapes. Remember to watch the water content in your brush and don’t over rub the pigment into the paper. Finally using big flat and round brushes lay on some dark values creating exciting and expressive areas of focus and interest. Keep working until you are using extremely dark passages of color and have really forced the viewer to move all around the paper. This lesson if done enough times will produce fabulous abstract results and give increased confidence with your brushwork and ability to apply paint.

(15 x 22 watercolor, I just let the brushwork flow using a Japanese brush.)

(15 x 22 watercolor, I just let the brushwork flow using a Japanese brush.)

Several more examples of paintings that emphasize experimenting with brushwork. See if you can get some more understanding of the power of the brush by really studying them.

(22 x 30 watercolor, “Stars in the night, South Africa” Shooting starts, satellites, and far far away.)

(15 x 22 watercolor, “Camden, Maine”, Lots of interesting line and marks created with a fast and loose approach with a brush. It is hard to use a brush like this without practicing first. The worst time to learn to do something is in the middle of your painting. I think the pier has a nice calligraphic and the entire painting was executed with a number 16 round brush.